What’s on tap? Maybe one day your wastewater.

Looking to history and around the world for examples, a picture of opportunity emerges from a wastewater problem.

Plato, Lao Tzu, Gandhi, Cleopatra – odds are that in your lifetime, you’ll drink some of the same water molecules that any one of these historical figures once drank. That’s because Earth’s water is a fixed resource, neither created nor destroyed. Century after century, eon after eon, water continuously mixes and recycles. Why then, do we think of wastewater as just that – waste?

In June, I talked about this conundrum and other aspects of urban waste management with environmental historian Matthew Booker and engineer Francis de los Reyes. The answer, it seems, is a lesson in history – and a call to challenge our assumptions about what we consider waste.

About a century and a half ago, I learned, people began moving into American cities faster than infrastructure could keep up. Packed and stacked in lively city blocks, people became vectors for diseases spread through contaminated water, like cholera, typhoid fever and dysentery. Epidemics claimed millions of lives.

Then people realized maybe water was the answer. Cities built pipes and dug canals that carried in clean water from reservoirs miles away and cast out dirty water to sewers for disposal or treatment. This separation of drinking and waste water prevented millions of deaths.

But we dumped something else out with the bathwater, Booker suggests. Once we labeled wastewater as a problem, we lost our ability to see it as an opportunity.

This unintended consequence of industrial age sanitation is relevant for how we manage waste now and into the future. Some 2.2 million Americans still live without running water or indoor plumbing. Globally, multiply that by 1,000. Around 2.2 billion people around the world lack access to safely managed water services, including 115 million mostly women and girls who collect drinking water directly from rivers or lakes. And people are still flocking to cities, putting pressure on aging water infrastructure. The United Nations estimates that nearly 70% of some 9.7 billion people – drinking, peeing, pooping people – will live in urban areas by the year 2050. As they migrate, climate change will continue to unfold, promoting ideal conditions for increased spread of disease. So the question remains: What do we do with all this waste?

First, say De los Reyes and Booker, stop calling it waste. Trade up and call it a resource. Swap a problem for a solution. Second, look back in time. Look out to others. There are plenty of examples in history and around the world of people who have tackled bigger challenges with fewer resources. Finally, reflect on what cleanliness and comfort mean to you. What would you be willing to adjust? Reframe wastewater as a resource, and it is no longer such a daunting problem.

The Long View Project recognizes that no single interview can paint a full picture of any topic. Rather, we hope this interview, edited for clarity, can serve as an entry point for a larger conversation.

No one wants to talk about waste management, it seems. Poop’s gross. But there is a huge waste problem that isn’t easing up. As the global population grows, more people are moving into cities – all while climate change unfolds before us. Why should we care? And what do we do with all this waste?

Francis de los Reyes III: We should care because it’s not going to go away. The fact of the matter is that there are billions of people around the world in less developed countries where the infrastructure is just not there to protect the environment and the public health of society at large.

This problem is also an opportunity. The way we think about waste is, it’s waste, the term itself. We’re trying to reframe it as “waste to resources,” “waste to energy.” Because somebody’s waste is somebody’s treasure. That really is true. We can think of waste as resources that are largely untapped.

The economy should be circular, not linear, where we use one thing, throw it out and that’s it. In a circular economy, everything is interconnected. We’re reframing waste to ask: How do we reduce the inefficiencies, the residuals, the actual waste? If we’re creative enough, we can make this work for us in a way that is more sustainable and will benefit people economically.

The way we think about waste is, it’s waste, the term itself. We’re trying to reframe it as ‘waste to resources,’ ‘waste to energy.’

Can you give an example?

de los Reyes: Think about poop. Globally, we produce a lot of poop. Think about wastewater. We produce around 400,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of wastewater every single day. Instead of treating that with very intensive processes and throwing that into a river or lake or the ocean, we can ask: How do we recycle that? How can we reuse it in a way that’s safe and saves money?

We should also care about waste because this is a human quality of life and dignity issue. Yes, billions of people all over the world don’t have access to clean drinking water or sanitation. But in the US, more than 2.2 million people don’t get clean drinking water at their house. Not addressing that costs the US economy about $8.6 billion a year.

Is that because of health costs?

de los Reyes: That’s health, impacts on the economy through reduced working time and all of those things, compounded. And it’s probably an underestimate. We don’t measure the secondary effects and generational effects.

Waste is also something we should care about because of the statistics. Economists have found that for every dollar we invest in water and sanitation, you get four or five dollars back. It’s a good investment. And it’s the right thing to do. There are those of us – hopefully the majority of the world, but maybe not – who believe that an equitable society is a better society across the board.

There’s a book called The Spirit Level, written by two epidemiologists. It lays out the data in the US and internationally. Drug dependence, alcoholism, debts, all kinds of bad things: The data shows that a more equitable society has lower numbers of all of these, so it’s a better society. And the smaller the gap between the very, very rich and the very, very poor, the better off a society is, across the board. I think that if we provide clean drinking water and sanitation services to everybody, it’s better for society as a whole. There are all of those other arguments, the moral, economic, and so on. But I think it just makes good sense.

From wastewater to drinking water: C’mon, the water’s fine

Matthew Booker: I’ve had the good fortune to work with Francis before. This moral imperative is so consistent with what I think drives Francis as an engineer. And it lines up nicely with the engineering imperative to be more efficient, to provide services equitably. That has been true for engineers for the last 150 years or so, since engineering was invented and professionalized.

I love to hear the way that engineers like Francis are thinking of using wastewater once again, and maybe even learning from places in the developing world where wastewater remains a really crucial, critical source for agricultural nutrients.

What lessons can we learn from others – across space or time – about reusing wastewater?

Booker: During the urban crisis of the late 19th century or the early 20th century, American engineers caught the ear of presidents like Theodore Roosevelt. He was totally inspired by engineering. That was his great metaphor for the work he did. “Efficiency” was the watchword of the progressive movement – and one of the greatest drivers of the huge investments in infrastructure in the late 19th, and especially early 20th century, in Europe, the United States and what we now call the developed world.

The enormous consequences for the economy as well as for human life then, a century ago, bear parallels to what faces the developing world today. There were epidemics of waterborne, waste-driven diseases. Cholera, for example, killed millions of American children in particular. The enormous success of that period is that they mostly successfully split the drinking water stream from the wastewater stream. That was the goal: The same water that people drank was not the same water their waste was going into, or, at least there was treatment in between those two things.

That had some negative consequences. One is that we (in the U.S and Europe) stopped thinking of waste, wastewater in particular, as an opportunity and not just a problem.

de los Reyes: Now, there are projects in California, for example, where they are treating the wastewater to the point where you can drink it. There’s direct and indirect potable reuse. Indirect potable reuse is when you treat it, and then put it into the environment, whether an aquifer, lake or another reservoir. Then you pull that water out and treat it for drinking water. That’s already happening. We now have the technology to do that. About 50% of Singapore’s water is wastewater that’s treated to the degree that you can drink it.

I would imagine Americans are hesitant to drink wastewater. How do they respond to the idea?

de los Reyes: Interestingly, in California, it’s moving beyond pilot scale. Of course, water issues from the drought a few years ago was a big, big driver. People were like, okay, we have to do this. We don’t have a choice. That has slowed down a little bit because it rained, and dams are full again. But those pressures will return, and we know that. I think people are more accepting now. With the right explanation, the right engagement of the public, the right messaging, I think people will accept it.

How does it taste? Have you tried it?

de los Reyes: No, but that’s a good point. When you say, how does it taste? Water tastes differently, depending on where you are. The water you grew up with probably is the best tasting water to you. It’s subjective. In fact, [North Carolina and others] have best tasting water contests.

But if you’re asking if you will taste anything funny – no, you won’t. Taste-wise, you won’t be able to tell the difference. It’s actually much, much cleaner than most. The treated wastewater from our modern wastewater treatment plants here in the US is cleaner than the drinking water in some countries.

Booker: At a California water conference at Stanford University in 2009 when I was a postdoc there, the water director for Orange County, California, was talking about this very question. Orange County has been water constrained forever, and they were real pioneers in wastewater reuse. They already had their first prototypes up and working. They were basically re-pumping aquifers, which was really efficient and interesting. They had the storage. It had to be reused again. Agricultural systems had already pioneered that technology, so they were just borrowing a set of behaviors.

What they were worried about was that people would freak out that they were drinking wastewater, so they were blending it. We had a fellow this spring at the National Humanities Center from Singapore, who brought up the water in Singapore. It’s blended. There’s always a mix of never-been-treated water plus treated water. He said that they have a really cool name for it in Singapore. “NEWater.” So, you know, let’s put marketers on it.

de los Reyes: You can even argue that part of Cary’s and Apex’s drinking water is wastewater from South Durham. Durham discharges to Jordan Lake. Cary and Apex take their water from Jordan Lake. It’s all a cycle. There’s a saying, the molecules of water we have today are the same water molecules that Jesus drank, or something like that.

What is “clean” anyway?

Booker: So much is about the story of how we imagine the world, right? Usually the way it gets framed is that there is something more natural and therefore safer, or more pure, about taking water out of a river, even if that water in the river is mostly wastewater from upstream. But in most of this country, and especially in this state, the water that’s in that river is likely to have already run through someone’s sewage system, possibly even their septic tank, which is less preferable than the kind of super treatment for drinking water that Francis is describing.

I never knew. Makes me not want to swim.

Booker: I see it differently. The world is less pure than we imagine it or want it to be, and the world that we helped create is actually safer. Just because we touch it, doesn’t make it bad. That’s a lesson from environmental historians: Leaning into the world we helped create is just fine.

Just because we touch it, doesn’t make it bad. That’s a lesson from environmental historians: Leaning into the world we helped create is just fine.

de los Reyes: The other point of that is: What is clean? How clean is clean? I don’t know how people define it.

If you think about it, nothing is really clean. Look at your bottled water. There’s always thousands, tens of thousands, of microorganisms in that bottled water. They’re typically not pathogenic. You’re not going to get sick. But it’s not absolute zero. Distilled water: You probably will not drink it for long because it doesn’t have electrolytes. It’s at the wrong pH, and there are all kinds of things that you need to put in the water to make it taste better and be better for you.

This concept of clean, there are levels to it. Obviously, we’ve set standards so that people don’t get sick. But at the same time, we should understand that there’s always stuff in it, and it’s not necessarily all bad. We can take it as humans. I mean, we’ve got hundreds of trillions of microorganisms in our gut anyway. We are more bacteria than human. We have more bacterial cells than human cells, more bacterial DNA than human DNA.

Sure, we may be part bug. But to stay healthy, we also have to fight, avoid, escape or exile the bad bugs – especially in the future when they may pose a greater threat to billions of people. What can we learn from the past diseases spreading in growing populations? What’s the talk about addressing this issue in the future?

Booker: It might be helpful to remember a few things about the near future compared to the not-so-distant past. I mentioned the late 19th and early 20th century. In most ways, those people had greater challenges than we do. I’ll just say that, again. In most ways, those people had greater challenges. And I mean people here in Raleigh and North America, but I think it’s transferable to most of the world at that point. The reason I say that is that people were changing fundamentally – not just how many people there were (there was a huge population boom underway for the last few centuries), but more importantly, where they lived and how they lived. In 1850 in the United States, there were just a handful of cities over 100,000 people. And in 1900, there were many cities with more than a million people. That’s just this country, which lags behind Europe and Asia, even parts of Latin America.

Now, just for example, think about the technologies for drinking water or agriculture and wastewater. How do people feed themselves? How do they shelter? How do they travel to work? What work do they do? We’re talking about much greater changes than the Internet. We’re talking about really major changes in the way people live, whether they produce their own food or whether they have to purchase it, whether they work in a small, family-run workshop or on a farm or in a factory with thousands of other people. All of that is so fundamentally transformed in a single to two human lifetimes.

The context here is that they figured it out. There was a huge amount of suffering, deaths from waterborne and foodborne illness. But there were also remarkable innovations that people sorted out really quickly – and they had some disadvantages compared to us.

They did not have the enormous pool of talent that we have, thanks to institutions like [NC State], or the worldwide sharing of knowledge that we have. They were much constrained in terms of how fast they could share information. There was also only limited taxation in the United States. Remember, it’s not until 1913 that income tax is constitutional, so the tools that they had available to them to resolve their crises – which were always, and remain, collective crises – were much limited compared to ours. They had to remake not just the physical world around them so it was livable, but they also had to remake the institutional, the governmental, and I think along with it, the philosophical world. They transform the Constitution of the United States, for example. In Europe, they change governments radically from monarchies into other forms.

I would just remind us that it can seem really daunting looking forward, but boy, did they deal with more than we have.

I would just remind us that it can seem really daunting looking forward, but boy, did they deal with more than we have.

About half of people live in cities now, which is up from the mid-20th century. By the mid-21st century, two thirds of the population will live in cities. Do you think that’s still not as big of a change?

Booker: Well, I mean, only in 1920 did 50% of the US population live in cities, and back then a city was a smaller unit. There’s good news and bad news about the continuing shift to urban spaces. The scary news is that we have to find ways to adapt these spaces, many of which have not been invested in in recent decades in the ways that people paid taxes and transformed their lives to pay for the future a century ago. A lot of our infrastructure is really aging and engineers and epidemiologists should really be listened to on this one.

The good news is that we know from anthropological work, from archaeological work and historical work and from more recent economic studies, cities are by far the most efficient way to serve populations. People use less energy. The spaces that we occupy in cities are much better equipped to deliver infrastructure efficiently. There’s actually less investment needed if we’re serving urban populations than if we were trying to provide the same quality of life to people in a distributed landscape.

So people urbanizing is an easier problem?

de los Reyes: I don’t know about easier, but I think it’s more efficient to house a lot more people in a city that’s more dense.

Yeah. Help a lot more at one time.

de los Reyes: Yes. You know, a city as an organism in itself, is much more efficient. You can provide services and infrastructure much more efficiently for a greater number of people.

The city as an organism

Matthew, in your discussions about the history of food in cities like New York at the turn of the century, you’ve mentioned “the organic city.” What is that? Is it kind of similar to the circular economy?

Booker: I think there’s a parallel. The historian Ted Steinberg popularized this notion of an organic city in a thoughtful essay. Steinberg was referring to this moment in the United States, particularly, when people moved into cities like New York, or San Francisco, or Chicago, or wherever, and doubled and tripled their size in a matter of a few years. I mean, San Francisco had fewer than 1,000 people in it in 1846. Gold was discovered in 1848, and by 1849 there were about 25,000. There would be nearly half a million people living in San Francisco – almost a million in the Bay Area – by 1910. We’re talking about massive growth.

Anyway, he was referring to the rapid growth of the old model – cities that were still producing mostly their own water and their own food, and also recycling their own waste to do it, through intensive agriculture. My discussions on oysters centered this in terms of aquaculture because of wastewater running off and increasing populations of people adapting to that by increasing numbers of shellfish that they could grow locally. That’s the organic city.

It would give way into the divided drinking and wastewater streams that we talked about, to a more modern city in which people don’t generally produce their own food. Most water within major metropolises does not come from within the local watershed. It has to be brought in from elsewhere.

The circular economy notion strikes me as something like the organic city. But I would just caution that the organic city was also the city of those massive cholera outbreaks. It was overwhelmed by its capacities. It needed help in order to adapt to the enormous influx of people.

de los Reyes: The circular economy doesn’t refer to circular, as in space, bound within the city. It refers to thinking of flows of materials and energy as things that you can reuse, recycle. So it’s not just a one-off, linear input-output, but the input of one becomes the output of the other.

I suppose what I found similar was that cycle of resources and waste. You’re growing food around you. You’re eating that. You’re pooping and peeing that out. You’re reusing that waste as fertilizer and water to restart the cycle. But that bred diseases then. Would it now?

de los Reyes: It depends. It would [spread disease] if we did not have the technologies and frameworks we have now or an understanding of what disease is. It’s only very recently that we understood what was causing disease, in terms of Pasteur and germ theory.

Booker: Germ theory isn’t taken up by most people, really, into the early 20th century. It exists as an idea, but it is not popular in policy. [Germ theory was developed and popularized between about 1850 and 1920.]

de los Reyes: Now that we know all of that, we can think of [reusing waste] in a different way. The way you described [the connection between a circular economy and the organic city] was really striking because you talked about inputs and outputs, pooping and peeing and getting resources. It’s really like an organism, isn’t it? I mean, basically, a city is like a living thing: I’ve got to get resources from outside, water and food and whatever. And then I produce waste that I need to take care of, whether I take care of it within the city, or have to take it out of the city. There are all these frameworks to think about it, but we do have the technologies now to protect public health, the environment within the city and also outside.

Do you think we could have that sort of organic city today where we’re producing food with our own waste? Do we want to? Is there a benefit to it?

de los Reyes: Yeah. I think that in some ways, we don’t have a choice. It’s going to be clearer in the next few decades that we’ve got to think of different ways. So for example, the way we think of water treatment and wastewater treatment has always been, we take water from this large reservoir. We treat it, put it into pipes and everybody has piped water at home, many, many miles away in the city. Then that wastewater is collected, again, in pipes, sewer lines, and it’s transported again, miles and miles, to a centralized wastewater treatment plant. Then that’s discharged to the river. That’s very linear. That model is not going to work for everybody. We know it’s not working for a lot of people already, those millions in the US and those billions around the world that we already talked about.

Are these people who are using wells? Why isn’t this system working for them?

de los Reyes: Some of them have wells, and some of them don’t. There’s a region called the Black Belt region in Alabama, for example, that doesn’t have a good way of disposing of their wastewater.

There’s just no infrastructure, or just outdated infrastructure?

de los Reyes: Yeah. They’re just out there in the rural areas, and septic tanks don’t work for them. What’s happening is they flush their toilet and it just goes to their backyard, like a cesspool.

We’re talking about colonias along the southern US border. We’re talking about Native American reservations, where they don’t have access to water, and so it’s dropped or they have to go out and fill up containers. We’re talking about communities in West Virginia. We are talking about folks in North Carolina, you know, cities or towns where, again, people rely on failing septic systems. We have all of these pockets of people and communities that have been left behind.

But in the future, imagine you have a house, and in your house, you have a little bit of input water. Maybe it’s rainwater. Maybe it’s from your own well. Maybe it’s even coming from the city. But right now, you’re flushing your toilet with clean drinking water. It’s basically the same water.

I didn’t know I could drink my toilet water.

de los Reyes: You could. The pipe to your toilet is the same pipe to your sink. It’s the same quality drinking water coming from the drinking water treatment plant.

That really doesn’t make sense because you don’t need to flush your toilet with clean drinking water. Imagine in your house, you flush the toilet with greywater, or treated water that’s not drinking water quality. And then your toilet water, your blackwater, goes through a different system. Maybe you can even shower with treated water. It’s literally circular within the house.

Imagine that your house is 95% efficient, and you only get 5% water coming in. The rest you are recycling within your house. That’s already happening. A high-rise apartment complex in New York City’s Battery Park City called The Solaire does this with a greywater system in the basement. They reduce the use of water by a lot more than 50%. [It reuses up to 25,000 gallons of wastewater daily.]

Imagine that your house is 95% efficient, and you only get 5% water coming in. The rest you are recycling within your house.

When I think of water treatment, I think of giant tanks and chemicals. But some homeowners are already swapping that for onsite greywater systems. What does it take to treat water onsite with this kind of system in a single-family house, or your ideal house of the future?

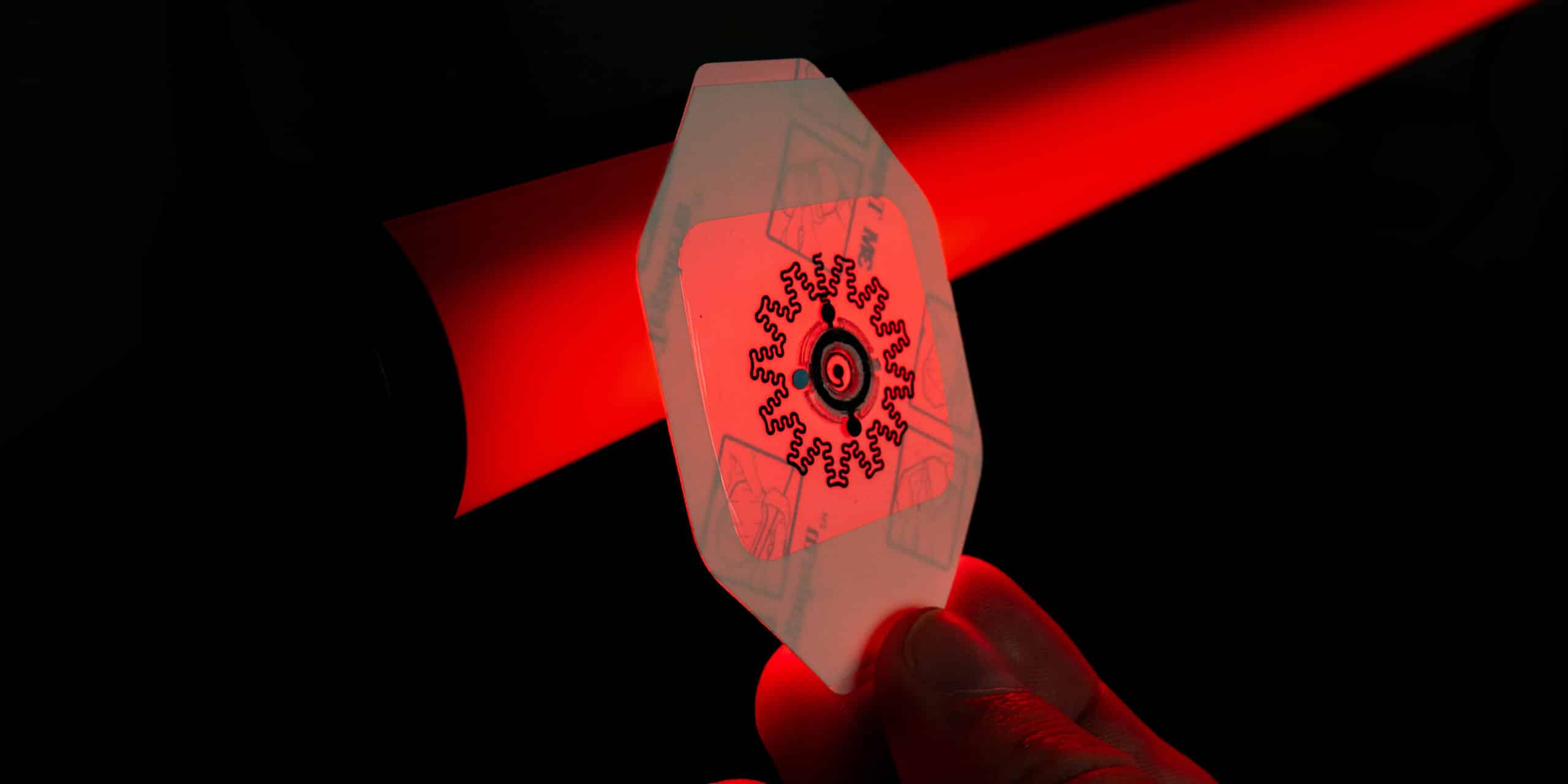

de los Reyes: It’ll be a unit the size of a refrigerator, maybe in your garage or basement. And you have a different set of pipes inside your house. You have different colored pipes, but not a lot more. There’s a pipe for the “yellow water,” which is the urine, and that goes through a different treatment than greywater from your sinks or blackwater, typically feces. Recycled water [generally for irrigation] moves through purple pipes. A study using Los Angeles as an example showed that for new construction, it adds roughly 1% of the cost of the house to have this dual-, triple-pipe, greywater treatment system [about $4,000 for a $400,000 home].

The return of toilet mania?

As far as toilets in this future water-recycling home: Does this also mean the urine-diverting or composting toilet?

de los Reyes: Yep. That’s one thing.

Would everybody in the future have these kinds of toilets? Is it something that could scale?

de los Reyes: Yes. Europe already has urine-diverting toilets. There are two holes, front and back. One is for urine, and one is for fecal material. That’s already happening – but it does require us to rethink the traditional model that we have now. It’s going to take a while for us to build that infrastructure.

I used one in a tiny home I stayed in. Composting or urine-diverting toilets are quite trendy in tiny homes. But can’t they get really expensive? Why would they be more expensive? Is that a supply and demand thing or a new technology thing?

de los Reyes: In general there’s this technology lifetime curve, an adoption curve. It is a demand thing.

It’s like the first computer we bought.

de los Reyes: That’s right. The first adopters always pay more because there are few of them. But they pay more because they’re first adopters. They’re the people who line up for the next iPhone.

They line up for the next toilet.

de los Reyes: But then the costs come down because we get better at this. We mass produce. There are economies of scale. That’s the general curve for any technology.

Booker: Nancy Tomes has a wonderful book called The Gospel of Germs on the adoption of toilets in the United States. It’s really a history of how people accepted Pasteur’s ideas over many years. His work was really in the 1860s and 1870s, and it wasn’t commonly accepted, so how did people actually take up these technologies? She refers to a sort of wave of mania for new model toilets. It is possible. As another example, Japan has very successfully marketed these immensely exciting and high-tech toilets.

I’d also point out that there are also some low-tech technologies that wouldn’t be suitable for an apartment building in New York, but are widely in use in the world today and were much more so in the past, that can be made more efficient and scaled up.

I grew up in rural northern California with, I guess I’ll call them “back-to-the-landers;” some people call them hippies. There was a whole scene in the closest town to where I grew up, Occidental California, of people investing in and really perfecting composting toilets. They were, of course, borrowing from technologies in widespread use in Asia and Latin America. But they were adapting them to an American context. For example, we don’t like smells.

Low water use systems are fairly common worldwide I think because water is not for wasting in most places. I lived for a year in Delhi, and we rinsed our toilets using a can of water. There was a tap handy, but there was no running water into the toilet itself. There are technologies that we could adopt if we were willing to change what we expect from our toilet experience.

What if we reimagine what toilets were? People reimagined what toilets were a century ago, when they adopted the water closet. How is that not possible for us to do now?

That might be part of the problem, too: What do we demand from our toilet? Francis pointed out that in this country, and in much of the developed world today, we somehow imagine that it’s okay, or normal, to pour drinking water down the toilet. That’s incredible. That is wrong. It’s wrong that we take this expensive and precious material and throw it away. In the process we’re thinning out the fecal matter so much in some of our systems, that it’s actually harder work for microbes breaking it down in the sewage treatment plants.

What if we reimagine what toilets were? People reimagined what toilets were a century ago, when they adopted the water closet. How is that not possible for us to do now?

de los Reyes: This is the behavioral and cultural side of things. Technology is technology, and then there’s the culture. The world is divided into washers or wipers.

Oh. I saw this in one of your TED Talks.

de los Reyes: I was a washer growing up in the Philippines. We had the same thing. And then I became a wiper when I moved to the US. Now I’m a hybrid. I have one of those bidet things. It’s cleaner. It’s touch free, you know? I look at myself, and I’m like, ooh, I’ve changed my practices over time.

A plight of pampered poopers?

Booker: Just one more time. Why do we think it so much harder for our generation to make major cultural changes than it was for our great grandparents? How are we so special and precious and fragile that we can’t make significant changes – even minor changes – in our day-to-day behaviors that will benefit our successors, our children, our grandchildren, great grandchildren? How can we not have some of the same fundamental moral obligations to them that our ancestors had for us?

Remember that most of the taxation and the burden for paying for these infrastructure systems fell on the people who started them. They were investing in the future a century ago, a century and a half ago. They built the water systems, the great aqueducts, for example, that supply San Francisco, New York and other cities.

de los Reyes: As engineers, when we design, we sometimes draw a line and leave the culture alone. If your solution relies on people having to change a lot of their behavior, then it’s probably not going to succeed. We tend to think we cannot change people. We’re engineers. We cannot do that other part, right? But more and more, the solution is somewhere in between, where technology meets culture – and both have to evolve. How do we address that?

If you think about the future of cities – the future of anything – we have to think about how people interact with technology and what they expect, what their responsibilities are and so on. It can’t be that we flush it. That’s it. We don’t care. That’s not the solution long term.

We tend to think we cannot change people. We’re engineers. We cannot do that other part, right? But more and more, the solution is somewhere in between, where technology meets culture – and both have to evolve. How do we address that?

Booker: The cultural and behavioral changes that Francis is talking about have happened in the past. This is not some crazy idea that we have to change how things have always been. I’m talking about remembering how things used to be. The great infrastructure in this country, and especially when it comes to public health and water and sewers: These were public investments paid for by the people a nickel at a time.

de los Reyes: But was that top down, too? Like, FDR also had to say, hey, let’s do this.

Booker: Right.

de los Reyes: So political will is involved, and visionary leadership is needed.

Booker: And even just a lot of forgetting. In terms of toilet habits, Japan also has a historical lesson in the adoption of the Western toilet after World War II. That was driven by a well thought out PR campaign.

Wait, what was their toilet before?

de los Reyes: Japan had dry toilets before they had these flush toilets and fancy toilets that spray water on you, the bidet.

Heated seats, colors….

de los Reyes: Warm seats and lights and music and beyond: Those are the modern toilets available now. But after adopting the western flush toilet after World War II, the bidet was introduced to the Japanese home. It was a well-thought-out campaign, especially during the early 1980s, that involved leading celebrities. They also tapped into this Asian and Japanese notion of cleanliness. [Check out The Big Necessity for more on this.] Now people can’t imagine a past where they were wipers using dry toilets. Advertising is not my area of expertise, but I do think that there are ways to influence the discussion and discourse more creatively.

Booker: We might need to make profound cultural changes in the next decades if we’re going to deal with climate change and have clean water and be equitable. And they’re really not that impressive compared to some of the cultural changes that have just happened almost overnight.

Is it tougher to get that kind of cultural shift with more people, like, it just becomes unmanageable to reach a consensus? I’m thinking of how divided we are, and just how much bigger the US is than when the country started out.

Booker: I think this would be a great place to talk to a behavioral psychologist or a behavioral economist. But I’m thinking in some ways, maybe it’s easier to change norms when you have the kind of rapid communication that social media affords.

Give a hoot and don’t pollute: Those kinds of campaigns move really fast now. You get influencers, you get the cool people acting, and rather suddenly you get dramatic change.

de los Reyes: Different drivers change individual behaviors and behaviors on a massive, societal scale. In California, the drought was a driver: We don’t have a choice. We’ve got to have water. The adoption of toilets? My understanding of the switch from outhouses to indoor toilets in the US (and of course, I wasn’t born then or here, so correct me if I’m wrong) is that it was driven by – ooh, my neighbor got a toilet inside their house. It’s almost like a “keeping up with the Joneses” kind of thing.

Destination Ideal Future: Stories, pictures and self reflection.

Imagine you can hop in a time machine and travel to your ideal urban waste future. What year do you arrive? And what do you see when you get there?

Booker: I want to make a plug here for artists. Artists will save us, as usual.

Once upon a time, science fiction writers called what they did “science fiction.” But in recent years I think some of the most interesting writers have been referring to what they do as “plausible futures.” Margaret Atwood said that she writes dystopias so we don’t have to live them – meaning that we might actually do something about the conditions that are akin to The Handmaid’s Tale if she describes it for us fully.

Another set of writers have been embracing utopian futures. I think they’re responding to their own political philosophy – that as a collective we’re more successful than as individuals – but also the absence of hope in much of the discourse, especially around climate change.

I want to plug Kim Stanley Robinson, in particular. He has been writing these books about plausible futures since the 1980s, including a wonderful series imagining three different futures for his home county of Orange County, California. A more recent book, New York 2140 is a post-sea-level-rise Manhattan story. It’s about people adapting. It’s not just about how much worse things are now that there’s water in the streets of New York. It’s also about how people have come together in the process of adapting to that disaster to resolve some problems that we hadn’t – equitable access to food, fairer labor, the control of people’s lives by a handful of authorities that they did not elect.

It’s an interesting idea: Solutions to some of the real problems we face, like climate change, might also address other problems that we face. What I love about his work and others’ is that these writers are giving us opportunities to rethink the assumptions we make about whether we should be flushing our toilets with drinking water, in the process of figuring out how to have safer sanitation systems.

So you’re OK with giving them control of the time machine, letting sci-fi writers describe what you may or may not see in the future? Or maybe they’re co-pilots?

Booker: People willing to imagine futures in that way are not burdened by, for example, the technical specifications that might restrain others. Francis, your imagination is limited because you know what is practical. I’m limited in some ways by what human beings have ever done before. But they’re free to mix those pieces and to be highly technical. With their creativity, all of us have a great opportunity to think.

The future is not so much about the systems that we need, as opposed to asking what’s going to be important to us as people, as humans. The why is always more important.

de los Reyes: A few weeks ago in a workshop we ended up talking about: How do we describe this future that we want? We were time constrained. We had maybe 15 minutes. So we asked ChatGPT. We said, give me an illustration that has these characteristics.

The first picture comes up, and it’s a city that looks like this. We looked at it, and we said, no, I think we want a little bit more green here. We want a little bit less of this, more of that. We did a few iterations until we got to a visual picture of what we thought was the future that we wanted. It was interesting that we had to think about it from a visual standpoint. What would it look like? It will have a lot more trees, a lot more plants. It will have people walking around, holding hands, doing stuff, enjoying leisure activities. It will have all of this cool looking infrastructure that seems to be more efficient. There’ll be things in the air, things underground. There’d be water. So it’s more of imagining it from those kinds of things.

You have to see it.

de los Reyes: You have to see it.

And the process. What I sensed was the four of us around the table feeding input to ChatGPT were reflecting what was important to us. I said, oh, we want more people there. We want more diverse people, walking around, enjoying a natural setting. The future is not so much about the systems that we need, as opposed to asking what’s going to be important to us as people, as humans. The why is always more important. Why are we doing all of these things? Because we want to have more leisure time. We want to spend more time with loved ones. As opposed to, I don’t know, being more efficient at your job. I’m not answering your question.

No. You both dodged it.

Booker: I think you are, though. You’re talking about: What is the world that you wish for? And then you approach the problem from the questions. How do we get to that kind of world? It’s the questions as opposed to the tools.

About the interviewees

Francis de los Reyes III is a sanitation activist, TED Fellow and Glenn E. and Phyllis J. Futrell Professor of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering and Associate Faculty of Microbiology at NC State University. His research focuses on wastewater, sanitation, and environmental biotechnology.

Insider recommendations: Read Richard Wilkinson and Anne Pickett’s The Spirit Level, which documents the connection between inequality and bad outcomes, Rose George’s The Big Necessity, a romp into human waste, or Chelsea Wald’s Pipe Dreams, a popular science writer’s take on the world of sanitation. For a more academic take, The Last Taboo by Maggie Black and Ben Fawcett. Watch the 2023 film Perfect Days, about a public toilet cleaner in Tokyo.

Matthew Booker is a Professor of environmental history at NC State University. His current research investigates food production in American cities during the Industrial Age and the history of aquaculture. His publications include Down by the Bay (2020) and, with Charles Ludington, Food Fights (2019).

Insider recommendations: Check out Nancy Tomes’ The Gospel of Germs for a look into how America’s understanding of germs developed. Read Annalee Newitz’ Four Lost Cities for a “long view on cities and environmental adaptation,” Ted Steinberg’s Down to Earth for how nature shaped American history, Martin Melosi’s The Sanitary City, and Mary Douglas’ Purity and Nature, exploring the modern “obsession with purity. She beautifully described our anxieties about waste and illness.”

This post was originally published in Provost's Office News.

- Categories: