Engineering students help Jones County improve resiliency

The six students are part of the first cohort of AmeriCorps assessment coordinators through the Coastal Community Resilience Immersive Training Program.

For six College of Engineering students, a summer focused on the coast meant a summer spent learning about how to support a coastal community working to improve its resilience to threats like heavy rainfall and flooding.

This summer, the community was Jones County, located about two hours southeast of NC State University and 30 miles from some of North Carolina’s most popular beaches. Students analyzed emergency response coverage, community engagement, social vulnerability, land utilization, land vulnerable to flooding and the effects of previous flooding caused by Hurricanes Matthew and Florence.

All six students are studying engineering:

- Lexy Boudreau, a sophomore industrial engineering and science, technology and society major;

- Sheridan Ely, a sophomore chemical engineering and Spanish major;

- Emma Hester, a 2024 graduate in environmental engineering;

- Roselyn Hopp, a junior industrial engineering major;

- Mckinley Richardson, a senior biological and agricultural engineering major; and

- Jack Voight, a senior environmental engineering major.

They presented their work during a symposium on July 19. Approximately 30 people attended, including faculty and staff members with the College of Natural Resources, the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, and North Carolina Sea Grant, as well as Conservation Corps North Carolina and the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management.

The six students are part of the first cohort of AmeriCorps assessment coordinators through the Coastal Community Resilience Immersive Training (C-CRIT) Program, a new partnership between NC State’s Coastal Resilience and Sustainability Initiative (CRSI) and Conservation Corps North Carolina. To learn more about the C-CRIT program, read more here.

Rebecca Ward, C-CRIT program director and CRSI postdoctoral research scholar, said the program was advertised across campus, but something about it appealed to engineering students.

“They really are problem-solvers, and they dove right in, rolling up their sleeves,” she said. “We’ll focus on engineering when we recruit future cohorts.”

C-CRIT’s goal is to train students to develop assessment maps and other key documents that can help coastal communities identify and prioritize coastal resilience projects, and to secure funding for them. A different community will be selected each summer.

Jones County, which is home to the towns of Trenton, Pollocksville and Maysville, has faced heavy rainfall and flooding that damaged schools, homes, businesses, roads and farmland over the last decade. In 2018, flooding from Hurricane Florence resulted in permanent school closures.

Local and state government officials, as well as Jones County residents, know that future storms will cause similar issues. By partnering with C-CRIT, they received help from the student cohort to enhance their ongoing work to be better prepared for future weather events.

None of the students had spent time in Jones County before. A few mentioned they had driven through on their way to Emerald Isle, North Carolina. But by the end of the 10 weeks, and after several visits to the county, they were familiar with local favorites, like the restaurant Aggie’s Pizza and Subs.

Most of the students had little experience with technical skills like GIS or with soliciting community feedback on their work prior to the program. They relied on the problem-solving skills learned in their engineering classes to approach the project thoughtfully and creatively.

“What I brought to this, from an engineering perspective, is not just looking at the one problem, but being able to look at it as a system of problems,” said Ely, the chemical engineering student.

The six tackled the project together, and each presented a poster on the area most interesting to them. Read more about each poster below (add jump link).

The symposium wrapped up with the students playing a climate change role-playing game called FutureScape, which was described as similar to Catan and Pandemic, but with role-playing, like Dungeons & Dragons. It was designed by NC State staff members and community partners for the spring workshop, Envisioning Transformations in North Carolina’s Coastal Plain

In the game, students applied what they learned over the summer to a North Carolina coast adapting to weather and global events in a sped-up timeline. They had 10 minutes for each round to reach a consensus on how to allocate resources or what protective coastal measures should be implemented. The students were lively, talking over each other until they agreed on a course of action — only to have their hard work undone in minutes by a natural disaster.

The 2024 posters:

Community Engagement: Strategies and Takeaways: Lexy Boudreau

Boudreau’s poster provided data on the team’s community engagement strategies and results. They met with county officials one-on-one, attended a board of commissioners meeting and invited county leadership to a meeting. They went to a local restaurant and a food pantry to poll residents on their top three environmental concerns, which were flooding and hurricanes, followed distantly by wildfires.

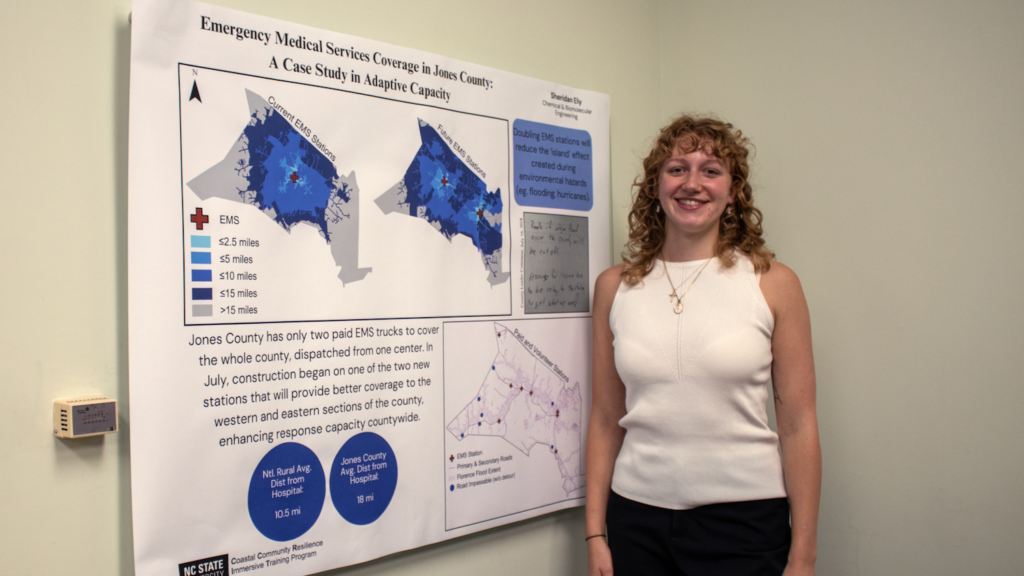

Emergency Medical Services Coverage in Jones County: Sheridan Ely

Jones County only has one 24-hour EMS station, which is based in Trenton, the center of the county. Some of the county’s population resides outside of a 15-minute response time. The county is currently constructing a new station and has plans for another new station. Ely provided data on how this broadens EMS coverage, as well as data to guide future decisions on expanding EMS capacity.

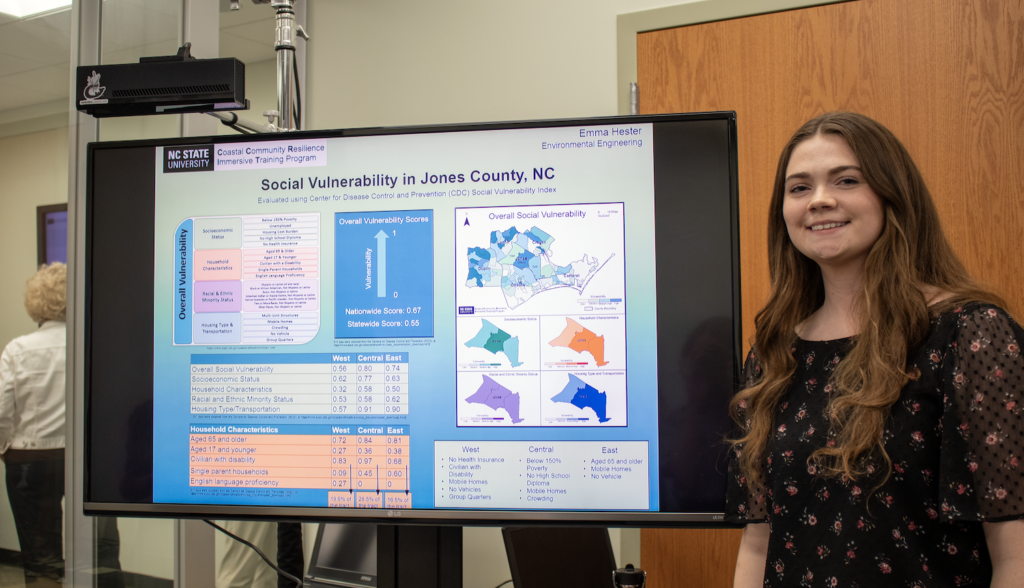

Social Vulnerability in Jones County: Emma Hester

Using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Social Vulnerability Index — which looks at socioeconomic status, household characteristics, racial and ethnic minority status and housing type and transportation — the team analyzed social vulnerability in Jones County. They found the county has a high percentage of people older than 65 and that many did not have vehicles, which could be an issue during evacuations. Hester said she would have liked to have more time to groundtruth the data by spending more time in the county talking to people.

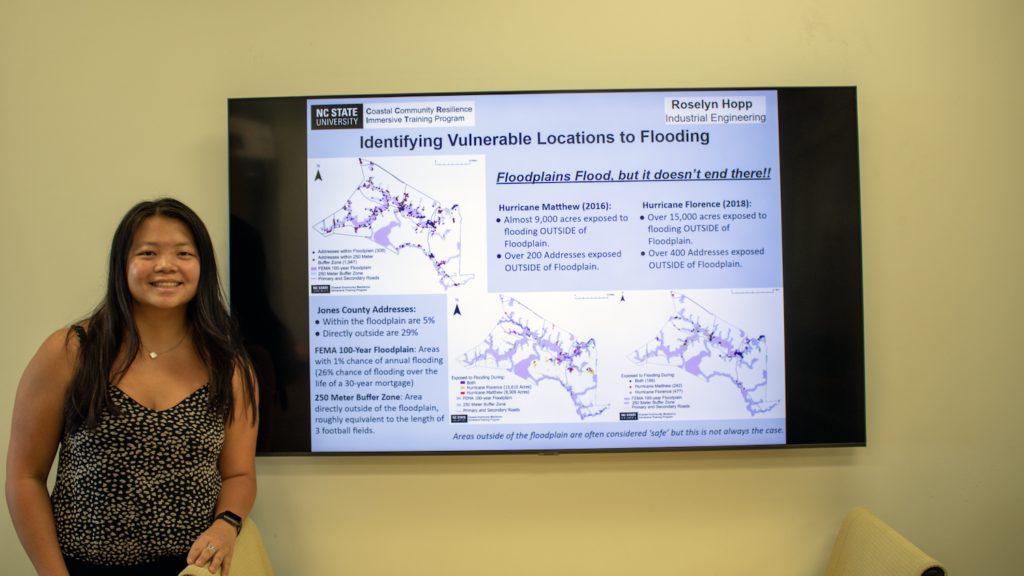

Identifying Vulnerable Populations to Flooding: Roselyn Hopp

Jones County has a designated floodplain, but it experiences flooding outside of that designated section. Hopp and the team looked at the 250-meter buffer zone outside of the floodplain, where 29% of the county’s addresses are located. During Hurricane Matthew (2016), 9,000 acres flooded, and during Hurricane Florence (2018), 15,000 acres flooded, and buildings outside the floodplain were destroyed. Having this data will help the county make decisions on where to build and how to protect structures vulnerable to flooding.

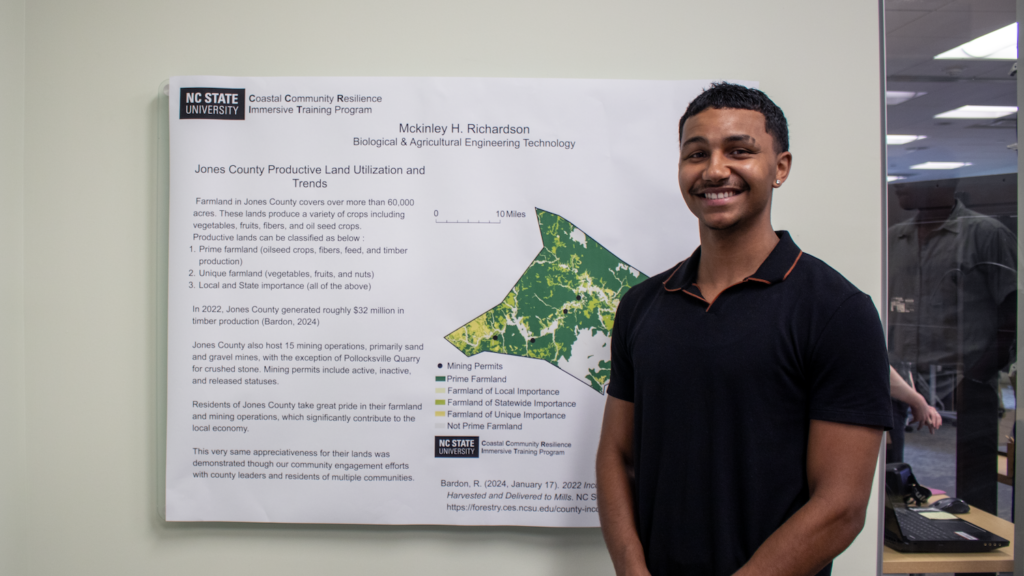

Jones County Productive Land Utilization and Trends: Mckinley Richardson

Farmland and sand and gravel mining are two important economic drivers in Jones County. There are over 60,000 acres of farmland that include prime farmland, where farmers grow oilseed crops, fibers, feed and timber, as well as unique farmland for growing vegetables, fruits and nuts. There are 15 mining operations. The team found that residents take a lot of pride in their farmland, Richardson said.

Hurricane Flood Extents in Trenton, Jones County: Jack Voight

Voight’s poster showed a map of where flooding occurred in Trenton, North Carolina, during Hurricanes Matthew and Florence. Both storms caused flooding in the 100-year floodplain, and flooding from Florence reached the 500-year floodplain. Two of Trenton’s schools were permanently closed, and the EMS and fire department had to be moved after Florence.