Recently discovered proteins may lead to new methods in creating biofuels

Researchers have found a very heated relationship between bacteria and newly discovered proteins.

These proteins are called tapirins and are capable of attaching themselves to plant cellulose, which could potentially provide more efficient methods of converting plant matter into biofuels.

Their name is derived from the Maori verb “to join.” Like their namesake, these proteins bind tightly to cellulose, a key structural component of plant cell walls, enabling the bacteria from which they originate to break down cellulose. The conversion of cellulose to liquid biofuels, such as ethanol, is paramount to the use of renewable feedstocks.

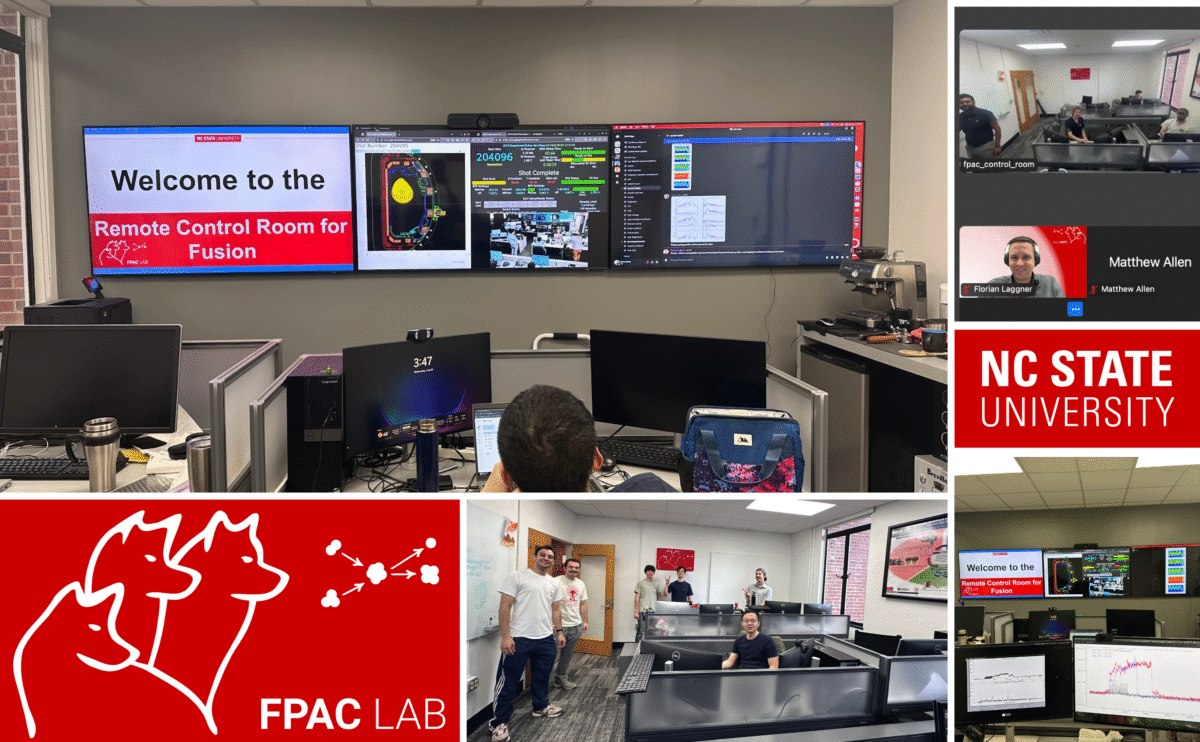

In a paper published online in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, researchers from NC State, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory report the structure and function of tapirins produced by bacteria that live in hot springs across the globe, including Yellowstone National Park. These bacteria, called Caldicellulosiruptor, live in temperatures as high as 70 to 80 degrees Celsius – or 158 to 176 degrees Fahrenheit.

“These hot spring scavengers make proteins that are structurally unique and that are seen nowhere else in nature,” said Dr. Robert Kelly, Alcoa Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and the paper’s corresponding author. “These proteins bind very firmly to cellulose. As a result, this binding can anchor bacteria to the cellulose in plant biomass, thus facilitating the conversion to fermentable sugars and then biofuels.”

In the study, the researchers showed that tapirins bind to Avicel, a cellulose powder that served as a test compound. The researchers also expressed the tapirin genes in yeast. Yeast cells with the expressed proteins attached to cellulose, while normal yeast cells could not. The paper also reports the tapirins’ crystal structure.

Kelly theorizes that, in places like the hot springs at Yellowstone National Park where food sources are rare, the heat-loving bacteria use tapirin proteins to scavenge plant matter that washes into the hot springs after heavy rains or snow melt.

Return to contents or download the Fall/Winter 2015 NC State Engineering magazine.

- Categories: